The Judge’s only son, William Fullerton, Jr., had a brief, but shining moment in the footlights as an expatriate composer of romantic songs and light opera, in the height-of-empire 1880’s London. They are clearly a study in contrasts: aggressively male father and sensitive, musical son. But both were well-known players at unique historical moments on opposite sides of the Atlantic. And perhaps if there had been a better accommodation between them, neither would have been so thoroughly forgotten later.

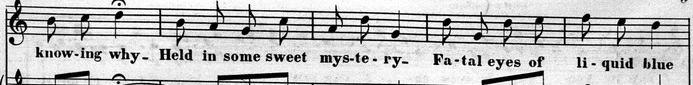

There are only scattered Willie footprints from his youthful New York years, but these provide a glimpse into gilded age NYC as well as the origins of the ‘Broadway’ Theatre District. Intentionally or otherwise, Willie left a roadmap to his personal relationships and ambitions on the front covers of published sheet music.

(as described in Rudolph Aronson’s, “Theatrical and Musical Memoirs”)

The earliest surviving piece, Silver Strains, is a waltz published in 1871. He was 17 and still living in Newburgh. The dedication reads simply: “To My Parents.” In 1865, Willie’s father had described in unmistakable terms a rigid, if idealized, view of a mother’s role:

While the husband is battling with the sterner duties of life, she remains at home to form the infant character…She is not only to guide the tottering footsteps, she is to guide the immortal mind. Her husband may go out into the world to win its wealth and honors, but she has a far higher sphere in which to act.

William S. Fullerton, Closing Statement, Millspaugh v. Adams.

Compared to the public lives of her husband and son, Cornelia Augusta Fullerton (like most women of her era) is both silent and invisible. But we can safely assume that she nurtured and encouraged Willie’s talents, and cannot entirely dismiss the possibility that she took some of the blame for whatever sorrow the old man felt over his only son’s choices and ultimate fate.

That Judge Fullerton could be both forceful and intimidating was well known to generations of witnesses and opposing counsel. Willie would pass away in 1888, at 34, consumed by a combination of tuberculosis, financial woes and distress over his inability to stage what was supposed to be his greatest work — the lost operetta “Waldemar: Robber of the Rhine.” Shortly after his death, sister Gussie wrote to her own daughter that Willie had once admitted he sometimes lay awake at night and cried when he felt their father was disappointed.

Still, during Willie’s boyhood, the busy trial lawyer was usually 60 miles away and mid-century Newburgh was a thriving place, filled with music. Adjacent to the bustling docks, the Water Street business district (utterly demolished during 1970s urban renewal) featured competing dealers who sold musical instruments, along with sheet music that could be brought home to fill evenings with intimate performances of song.

The emerging middle class was buying pianos. Although professional musicians and actors were not considered respectable, any well-bred young lady was expected to play an instrument and entertain friends, family and gentlemen suitors. Up and down the Hudson Valley, there were home-grown composers writing waltzes and military-style marches, and the public calendar was full of orchestral and choral group performances.

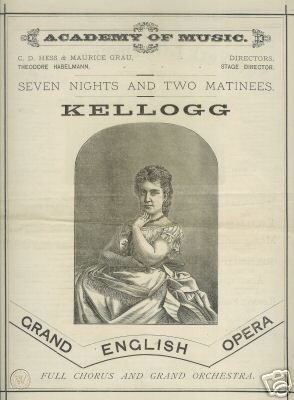

But Willie clearly had his sights on bigger things. His next surviving piece, Waltzes Marguerite, was published in 1873. The title as well as the dedication at the top of the cover page — “to Miss Clara Louise Kellogg” – speak volumes.

Fullerton Jr. ‘s intended public would have known that ‘Marguerite’ referred to the leading female role in the opera Faust, by French composer Charles Gounod, and that Clara Louise Kellogg (1842-1916) was a home-grown opera star, an internationally popular prima donna who had been born in South Carolina and raised in New England. In November 1863, 21-year old Kellogg performed the role of Faust’s ill-fated love interest in the opera’s American debut at New York’s Academy of Music. Her Marguerite catapulted the lyrical soprano to stardom, brought crowds to the Academy of Music on 14th Street (demolished in 1926), and helped establish opera’s place in New York City, just beginning to emerge as a cultural capital.

Marguerite was an early, signature role, and Kellogg also performed it in her London debut in 1867, at Her Majesty’s Theatre. By 1873, Kellogg had moved on to other challenges. In a memoir published 50 years after the first American performance of Faust, the world-weary diva wrote: “Musically, I loved the part of Marguerite—and I still love it. Dramatically, I confess to some impatience over the imbecility of the girl.” But 19-year old Willie — a descendent of hardscrabble, revolutionary war era farmers — was paying homage to Kellogg as a reverse pioneer — a ‘made-in-the-U.S.A.’ songstress who achieved widespread acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic, as he himself would set out to do.

Kellogg’s 1913 memoir also offers a glimpse into an exclusive, private musical world that Judge Fullerton’s son must have found enchanting:

In the seventies, New York was interesting musically, chiefly because of its amateurs…at that time, New York had a collection of musical amateurs who were almost as highly cultivated as professionals. It was a set that was extremely interesting and quite unique; and which bridged in a wonderful way the traditional gulf between art and society.

One of these glittering, gilded age amateurs was Mrs. Peter “Fanny” Ronalds, who would have a considerable influence on Willie’s career in London. To Kellogg, these talented socialite-singers “combined music and society in a manner worthy of the great French hostesses and originators of salons.” And in time, William Fullerton and his life-companion, artist and costume designer Percy Anderson, would host their own bohemian salon in London, where musicians and actors would mingle in an unrestrained atmosphere that would have been shocking back in Newburgh (and possibly in Manhattan as well).

But young Will Fullerton was under pressure to undertake a serious career. Law was something of a family business. His father and two of his uncles were attorneys. Willie’s sister married a promising young lawyer who joined Judge Fullerton’s law firm (but unfortunately died young), and an older cousin, Captain Stephen Fullerton, had been a promising attorney and politician whose brilliant prospects were cut short when he died from illness contracted in a Civil War army camp.

Plus, there was one more role model in Willie’s own generation. One of his father’s law partners, Benjamin Dunning, had named his son after Willie’s dad. That dutiful son, William Fullerton Dunning, went on to graduate from Columbia Law School and became an outstanding New York practitioner. But Willie steered clear of the well-worn path.

The records of Columbia University’s School of Mines (precursor to today’s Columbia School of Engineering) show that 20-year old William Fullerton, Jr. enrolled in a preparatory program for the academic year 1874-1875. Willie organized their annual December dance – the height of the year’s social calendar for those eligible bachelors. The surviving dance program includes a long list of Waltzes (nearly all predictably by the Waltz King, Johann Strauss II, but there was, of course, a performance of Marguerite Waltzes, by William Fullerton, Jr.

It is difficult to imagine that young Fullerton had in mind a career of designing or operating machinery or transportation networks. But if Newburgh was not widely known for its musical offerings, the opposite was true for its architecture, much of which was in the immediate neighborhood of the Fullerton home. Newburgh’s most famous native son, A.J. Downing (1815-1852), is sometimes described as the “father of American landscape architecture.” He died two years before Willie was born, but his lost gothic revival mansion, Highland Garden, was still standing a mere block away from the Fullerton family home.

The genesis of the Greensward Plan, which became New York City’s Central Park, began when Connecticut gentleman farmer Frederick Law Olmsted met Downing’s junior partner, young English architect Calvert Vaux, at the Downing home. Even today, the Grand-Liberty-Montgomery Street corridor is a showcase of 19th American architectural design, where surviving homes and churches reflect the vision of Downing’s peers like A.J. Davis and Thornton Niven, as well as Vaux and Downing’s other U.K. import, Frederick Clark Withers.

It is probably coincidental that Vaux’s son, Downing Vaux, as well as Olmsted’s nephew and stepson, Owen, attended the Columbia School of Mines at the same time as Willie. But the School of Mines offered many possible career avenues, including architecture, which was folded into their curriculum until the establishment of Columbia’s vaunted School of Architecture in 1881.

School of Mines was a tough program – rigorous and rigid. A student could fail a course simply by coming late to class. Young Downing Vaux dropped out and so did Willie.

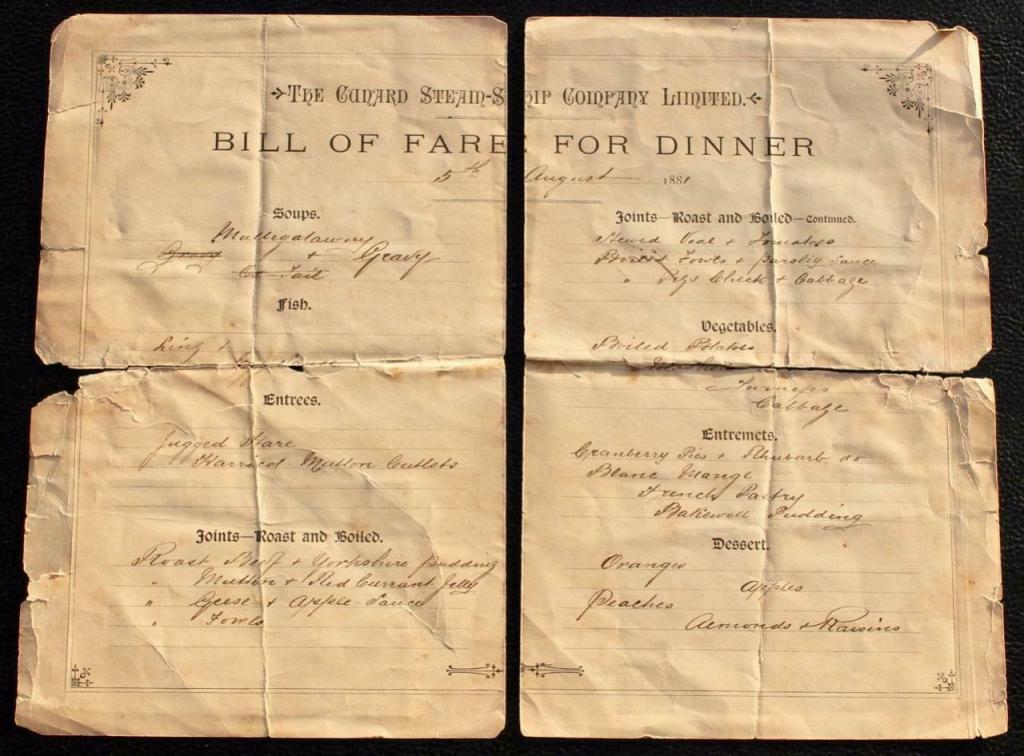

A year later, in 1876, Willie applied for a passport. Records show that he crossed the Atlantic to Liverpool twice — in 1876 and again in 1878. His concerned father may have followed him abroad (or at least prepared to do so). William Fullerton, Sr. applied for his own passport in 1877.

There is a peculiar discrepancy between American and English versions of Willie’s European education. English reviews of Willie’s music from the 1880’s referred to his studies at Leipzig’s renowned Conservatory of Music. But certain biographical sketches of the prominent American lawyer William Fullerton state that his son studied in Heidelberg (a major institution for science and engineering). Perhaps Willie tried Heidelberg, or told his parents he was doing so, in 1876, before undertaking studies in music composition at Leipzig, beginning in 1878.

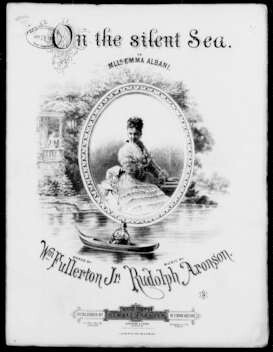

The next surviving scrap can be found in the sheet music archives of the U.S. Library of Congress: On the Silent Sea (1877), composed by Rudolph Aronson, with lyrics by William Fullerton, Jr. The title evokes the trans-Atlantic steamship passages that were an essential element of the burgeoning cultural exchanges between New York and the Old World, something he and Rudolph would have known well of by 1877. And Silent Sea’s dedication — to Mlle. Emma Albani — is a sort of a matching book-end to the 1873 homage to Kellogg.

Kellogg’s 1913 memoir traces her own 1867 glimpse of Mlle. (later Dame of the British Empire) Albani (1847-1930), in London. The celebrated diva had gone to check out the rival company at Covent Garden, where the competition included ”a pretty, young, new singer from Canada with them…who had a light, sweet voice and was attractive in appearance.” Like Kellogg, French-Canadian Albani was a successful North-American cultural export into the demanding European market. The sheet music salutes to these two divas clearly point in the direction of Willie’s own hopes.

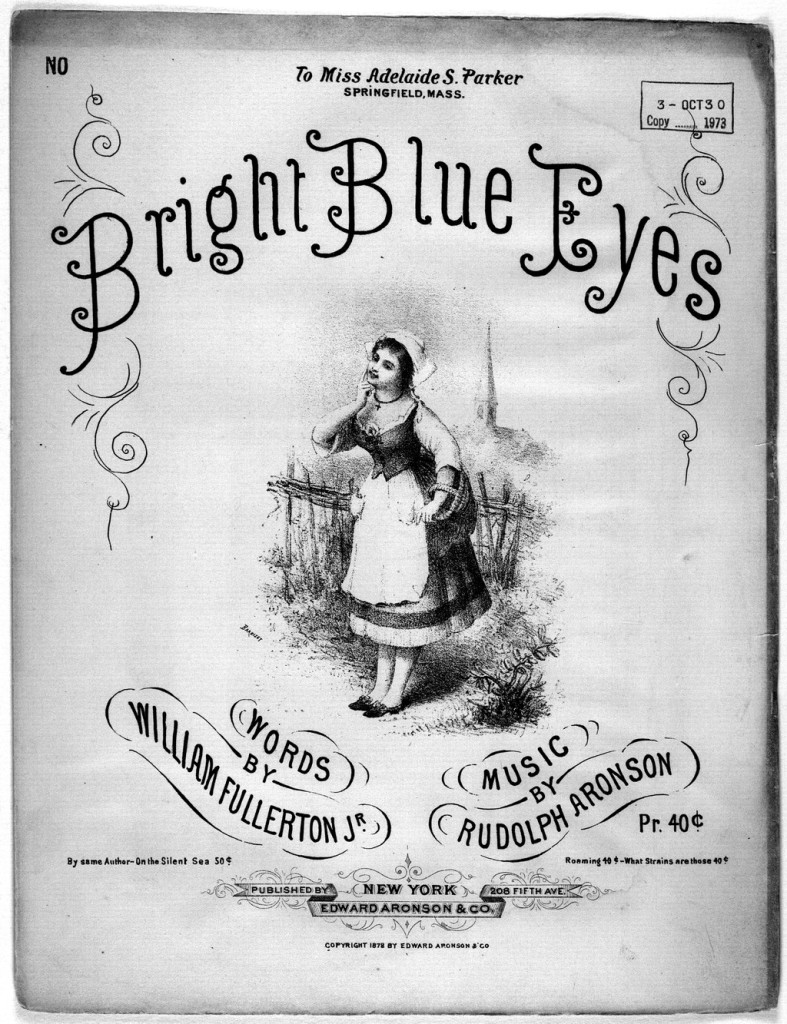

The U.S. Library of Congress has a second Fullerton/Aronson collaboration, Bright Blue Eyes, published in 1878. Rudolph Aronson (1856-1919) was an orchestra leader and composer – aided at the time by the music publishing business of his younger brother, Edward. But by 1878, as 24-year old Willie Fullerton was leaving New York for good, on the ship Abyssinia, Aronson was turning his attention to a different kind of role – raising funds to build the Casino Theater, a lavishly decorated Moorish revival palace at 39th and Broadway. The now-lost Casino Theater became an important home for the production of light opera and musical comedy for nearly fifty years.

There are no other known instances of Willie writing lyrics, and no evidence of a continuing connection between the two men after Willie settled in London, and went on to produce a major work of his own, Lady of the Locket. Curiously, it was not Aronson, but his erstwhile business partner-turned competitor, ‘Colonel’ John A. McCaull, who would later purchase the American rights to William Fullerton’s now-lost operetta Waldemar, and broadcast loudly his intention (never-fulfilled) to bring Willie’s work home to his native New York.

19th century Postcard

Notes on further reading:

Many theatrical figures published memoirs which — with due allowance for the authors’ biases, settling of old scores, and the vagaries of memory — provide wonderful period pieces. These include:

Albani, Emma, Forty Years of Song, Toronto, Ontario, The Copp Clark Co., 1911. Aronson, Rudolph, Theatrical and Musical Memoirs, New York, McBride, Nast, and Co., 1913. Kellogg, Clara Louise (Mme. Strakosch), Memoirs of an American Prima Donna, New York and London, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1913.

For musical theater history, all paths lead to Kurt Ganzl, whose vast output includes Encyclopedia of Musical Theater (Schermer Books, 1994) and the earlier, groundbreaking British Musical Theatre (Oxford University Press, 1986). Without Kurt’s writings, as well as his guidance and encouragement, research into lost composer Willie Fullerton would have been next-to-impossible.

As to Newburgh’s rich C19 architectural heritage — the definitive book remains to be written.

Many thanks to Research Assistant and Images Editor Jessy Brodsky for her invaluable contributions to this post.