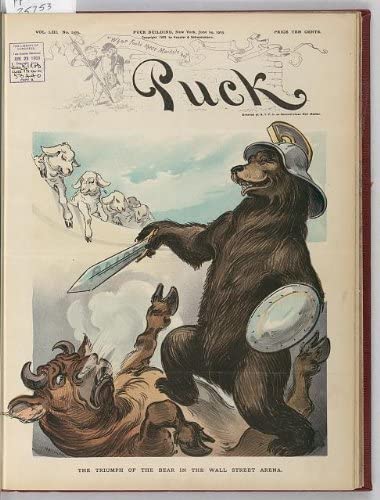

Short selling’s long history. History lovers can find distant echoes in pretty much anything that happens. Take the recent GameStop roller-coaster, in which a group of posters on the Reddit website tried to harness the power of social media to engineer a massive ‘short squeeze’. It’s a bit mystifying that this gang of speculators sold themselves as a populist revolt against Wall Street tyranny—it’s well-known on Wall Street that no one really likes short-sellers; for one thing, they are too negative.

But it’s surely noteworthy that two great short-sellers whose shadows loom large over 19th and 20th century financial history both died broke. Let’s work our way backwards.

Death of an Icon. The most famous American short-seller was Jesse Livermore (1877-1940). He reportedly made $100 million ($1.5 bil today) in the stock market crash of 1929. As a result, while much of the nation was struggling to survive during the Great Depression, the legendary trader was living the high life, at least until he squandered everything.

After a wild decade that included two divorces and three bankruptcies, in November 1940, Livermore fatally shot himself in the head at Manhattan’s luxurious Sherry-Netherland hotel.

Corner of the Century. Among the many ironic twists in this spectacular antihero’s story—back in 1922-1923, Livermore joined the bulls (those who, in contrast to the short-selling ‘bears’—drive up the stock) in a GameStop precursor: the Piggly-Wiggly short squeeze.

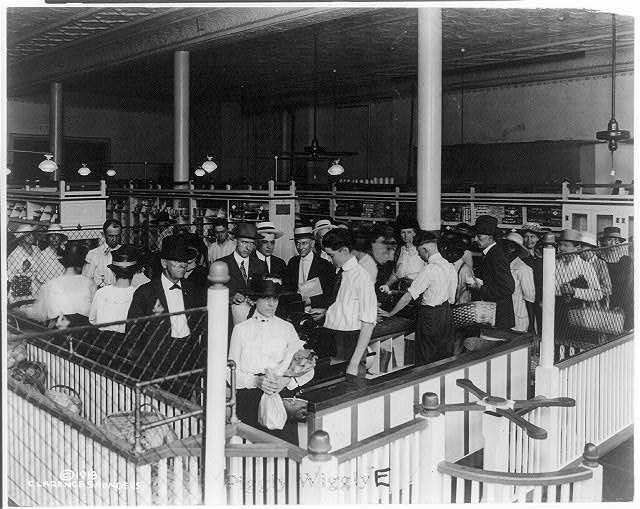

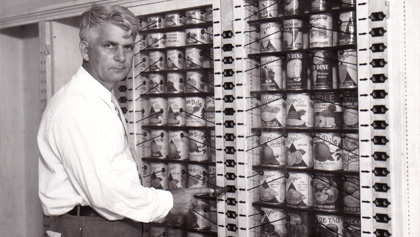

Clarence Saunders of Memphis Tennessee opened the first Piggly Wiggly in 1916. In essence, it was the first supermarket—a ‘self-service’ store in which customers were no longer required to hand their orders to clerks. By 1922, the business had grown rapidly and Saunders took it public. But an aggressive expansion effort resulted in some franchisee bankruptcies in the North-East. Seeing a potential profit, a coordinated group of Wall Street traders began driving down the stock price. An irate Saunders borrowed $10 million ($150 mil today) and recruited Livermore to create a ‘corner’ and counter the ‘bear raid’.

Much like the Reddit revolutionaries of 2021, Saunders used the media (back then—newspapers) to portray his cause as a Main Street crusade, pitting America’s small investors against the Wall Street establishment. By March 1923, he appeared to be winning. The stock had risen from a low of 39 to 124. But the New York Stock Exchange stepped in and halted trading, giving the shorts time to find shares to cover their positions. Saunders went bankrupt.

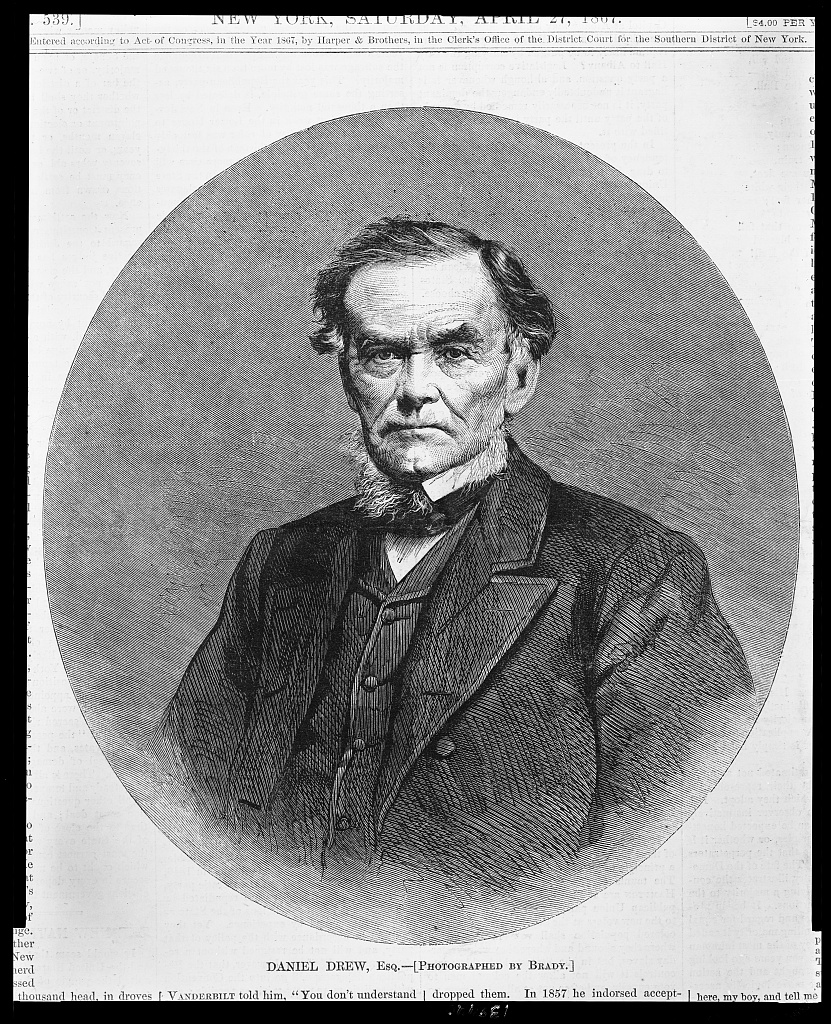

The Pioneer. Livermore was preceded, however, in riches and in drama by a largely forgotten figure who would pave the way for future generations of short-sellers—Daniel Drew (1797-1879). Unlike Livermore, Drew was devoutly religious with a stable family life. But he was utterly unscrupulous in business; his sneakiness became the stuff of folklore. One probably apocryphal story has Drew ‘accidentally’ allowing a scrap of paper with a false stock tip to fall out of his pocket.

Drew grew up in dire poverty in Carmel, New York, but discovered Wall Street, still in its infancy, as a cattle drover. Hard work and shrewdness paid off, and he soon owned the leading marketplace for beef cattle in New York City, the Bull’s Head Tavern on 23rd Street. But stock speculation was his true destiny.

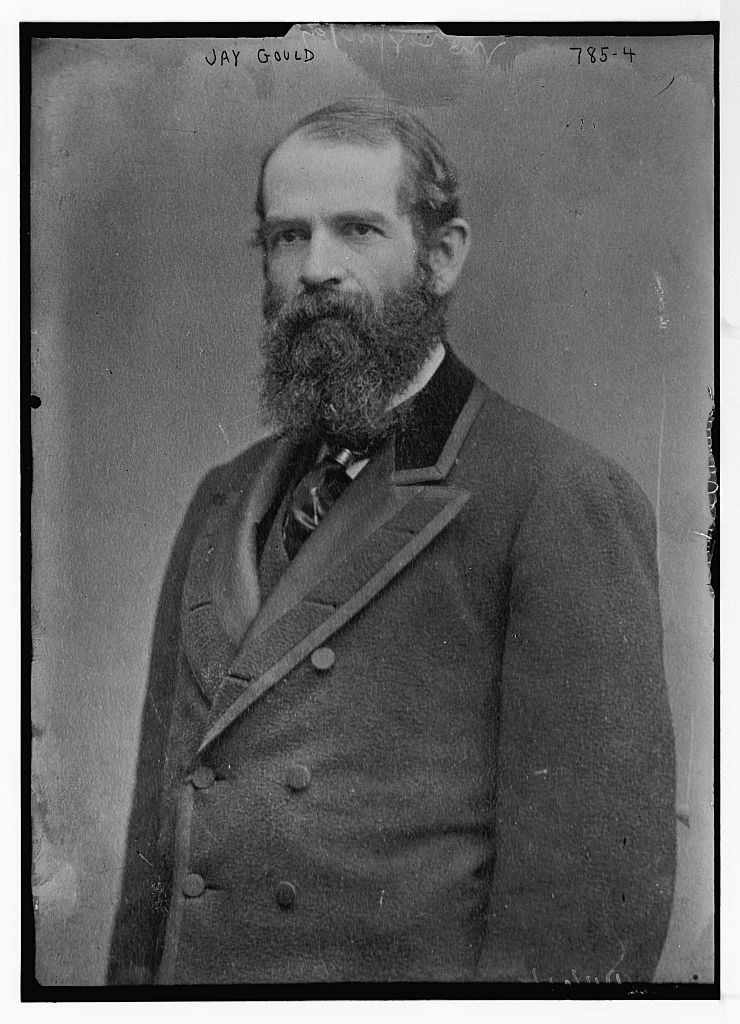

Clashing Barons. It was not a public crusade, however, that would undo the magnificent speculator. Rather, it was the combined effort of an unholy trio—‘Commodore’ Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jay Gould and the flamboyant ‘Jubilee Jim’ Fisk. These men were the first of the “robber barons”: transportation magnates whose naked pursuit of wealth helped set the tone for the entire Gilded Age.

In the 1830s, the Hudson River and the Erie Canal combined to provide the most important transportation routes for the growing national economy. Drew controlled a major steamboat line connecting Manhattan with the canal’s Albany-Troy terminus. But he found himself in a fierce rivalry with Vanderbilt. The on-and-off relationship between the two men would continue for over forty years.

During that time, the Commodore would become the richest man in America, mythologized for tying immense wealth inextricably with the American dream. Meanwhile, Drew also met and mentored a younger, unboundaried dreamer: Jay Gould. Eventually, Gould would control the first transcontinental railroad. But first, there would be fierce corporate warfare in New York.

Railroad Wars. Everything began shifting around 1850 with the railroads. It was obvious that profits would be elusive without monopoly pricing power. And so, there were endless struggles for dominance. As for Drew, by 1864, he was part of a group who was short-selling the New York and Harlem. At the time, though it was the only direct line into Manhattan, it was poorly run and undervalued. Vanderbilt saw an opportunity to buy control on the cheap and cornered the market in the shares. Drew lost $500,000 (over 8 million in today’s dollars).

The real action, though, was in the Erie Railway, which offered a land route between the docks at Piermont, NY and Lake Erie. Until the rise of the transcontinentals, it was the leading connection between the Eastern Seaboard and the vast agricultural and commodity riches of the Midwest.

Naturally, the Erie was a devil magnet, with a board that eventually included Drew, Vanderbilt, Gould and Fisk). The control contest became known as the Erie War. It was the first major takeover battle in American corporate history and is possibly still unsurpassed for its complexity and outright malfeasance.

Drew’s own habit of buying and selling Erie stock while serving as the company Treasurer earned him the nickname the “speculative director” in a later exposé. But it also set him up for another short-squeeze from which he never recovered.

At first, it was an 1868 Drew-Vanderbilt rematch, with an obvious revenge motive. And Drew initially got the better of his old adversary by conspiring with Gould and Fisk to water down the Erie stock, and relocating the Erie board temporarily out of New York jurisdiction. But by 1870 Gould and Fisk had joined hands with the Commodore and cornered Drew into a loss estimated at $1.5 million (over $29 mil today).

Trader’s End. A few years later, the Panic of 1873 forced the aging high-stakes gambler into bankruptcy. He had to renege on promises to beloved religious and educational institutions, including Drew Theological Seminary (today’s Drew University in New Jersey) and Drew Ladies Seminary in Carmel, NY.

Instruction was ended by 1952.

Following the death of his wife and loss of his Putnam County homestead, Drew moved in with his son at 3 West 43rd Street. According to his leading biographer, at age 81, he could still be seen haunting the trading floor, where his “his gray eyes [having not] lost their fire, occasionally glint[ed] with the joy of a small ‘killing’ that would give him pocket money.”

He is buried with the rest of his family at Drew Cemetery in Brewster, NY.

******************************************************************************

For further reading, Livermore’s wisdom for stock traders has been enshrined in the classic 1923 text “Reminiscences of a Stock Operator.” For a definitive biography of Drew: Browder, Clifford. “The Money Game in Old New York,” Lexington, KY, the University Press of Kentucky, 1986.

But for any reader thinking about taking up the grand game, consider another time-honored Wall Street adage—“Bulls make money; bears make money; pigs get slaughtered.”