The purpose of playing….to hold, as ‘t were, the mirror up to nature…and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure. William Shakespeare, Hamlet

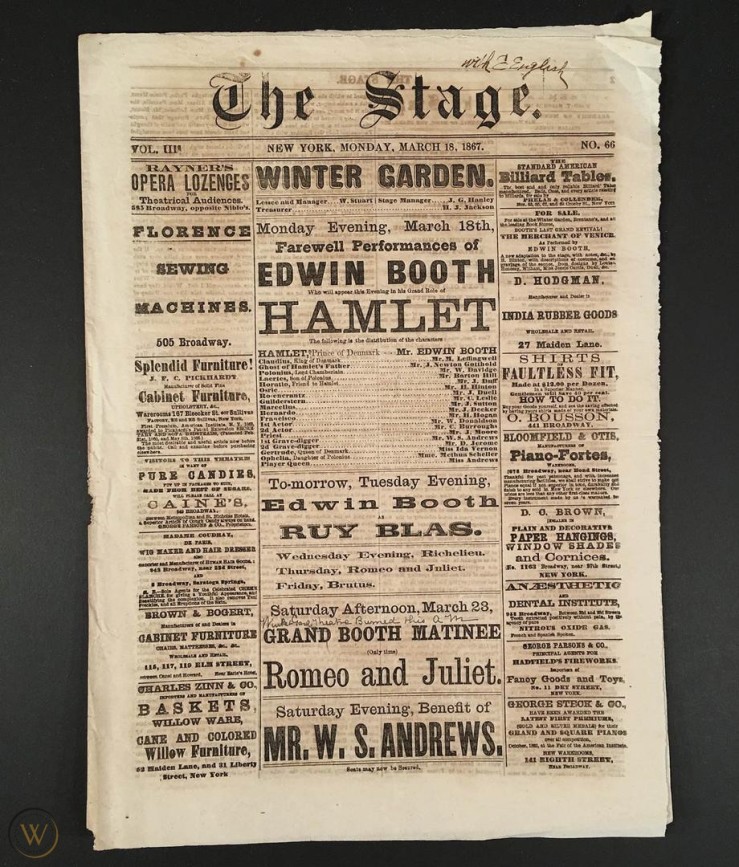

On January 22, 1867, a grand affair took place at Manhattan’s Winter Garden Theatre, located in the heart of Greenwich Village. Following a production of Hamlet, the stage was re-configured as a drawing room, where a select group of dignitaries emerged to greet the actor Edwin Booth. Musicians from all of New York’s principal theaters came together to play the Danish national anthem, after which Booth was given a specially designed gold “Hamlet” medal.

A confluence of themes came together in that celebration. It was New York’s way of announcing to the world (and especially its perennial rival Boston) that it had arrived as a cultural capital. It was also a message of post-Civil War reconciliation — that the beloved actor would not be held responsible for the sins of his younger brother, Lincoln’s despised assassin, John Wilkes Booth. And implicitly, it was a nod to the acceptance of theater — at least in the high form represented by Shakespeare — as a legitimate, elevated form of entertainment. Centuries of Calvinist-Puritanical preaching was being inexorably swept in the direction of the trash receptacles.

An assortment of dignitaries and cultural figures filled the stage. New York Governor John T. Hoffman was joined by Civil War heros — Major General Robert Andersen (commander of Fort Sumter) and Admiral David Farragut. The ad hoc award committee included the journalist Charles A. Dana and the painters Albert Bierstadt and Jervis McIntee.

For reasons that are not recorded, the medal was presented by attorney William S. Fullerton, whose speech singled out Booth’s “life-long efforts to raise the moral standards of the drama.”

The sad mystique of Booth’s Hamlet had been captured by the writer George William Curtis in April 1865, following a then-record run of 102 performances:

Throughout the whole play, the mind is borne on in mournful reverie….under all, beneath every scene and word and act, we hear…the melancholy music of the sweet bells jangled, out of tune and harsh….The cumulative sadness of the play…is a spell from which you cannot escape.

The Winter Garden Theater, which had been Booth’s main venue in New York, was destroyed by a fire only a few months after the Hamlet medal ceremony. The actor then built his own Booth’s Theater — an ornate Second Empire palace — at the corner of Sixth Avenue and 23rd Street. It was never profitable, and in time the building became McCreery’s Dry Goods. The building was tragically demolished in 1975 to make room for a parking lot.

The great actor’s footprints can be found all over Manhattan. The Shubert Organization’s Booth Theater on W. 45th St. is a theater district mainstay. Central Park’s statue of Shakespeare was built in part with funds raised at an 1863 Winter Garden benefit performance of Julius Caesar, in which Edwin starred alongside both of his brothers — Junius Booth, Jr., and the infamous John Wilkes. Booth’s own statue is located in Gramercy Park. Nearby, the Player’s Club, which Booth founded in 1888, still occupies its Stanford White-designed building, and maintains a memorabilia-filled Edwin Booth bedroom.

We don’t know whether Fullerton arranged for his wife Cornelia, or daughter Augusta (“Gussie”) or son William, Jr. (“Willie”), to come down from Newburgh for the performance and presentation. Perhaps 12-year old Willie was there, and came away starry-eyed. In the 1880’s, Judge Fullerton’s expat son would have a flickering moment of theatrical fame in London. A surviving playbill from Willie’s whimsical 1885 operetta, Lady of the Locket, does not exactly suggest the ‘high moral standards’ publicly espoused by the old man.

Unlike Booth, few traces of Judge Fullerton can be found in the frenetic city of forgotten greats. But the stories still hover in the bustling atmosphere, like restless spirits that cannot lie in peace until their secrets have been revealed.

For further reading: http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2010/06/shakespeare-comes-home-to-23rd-and-6th.html]